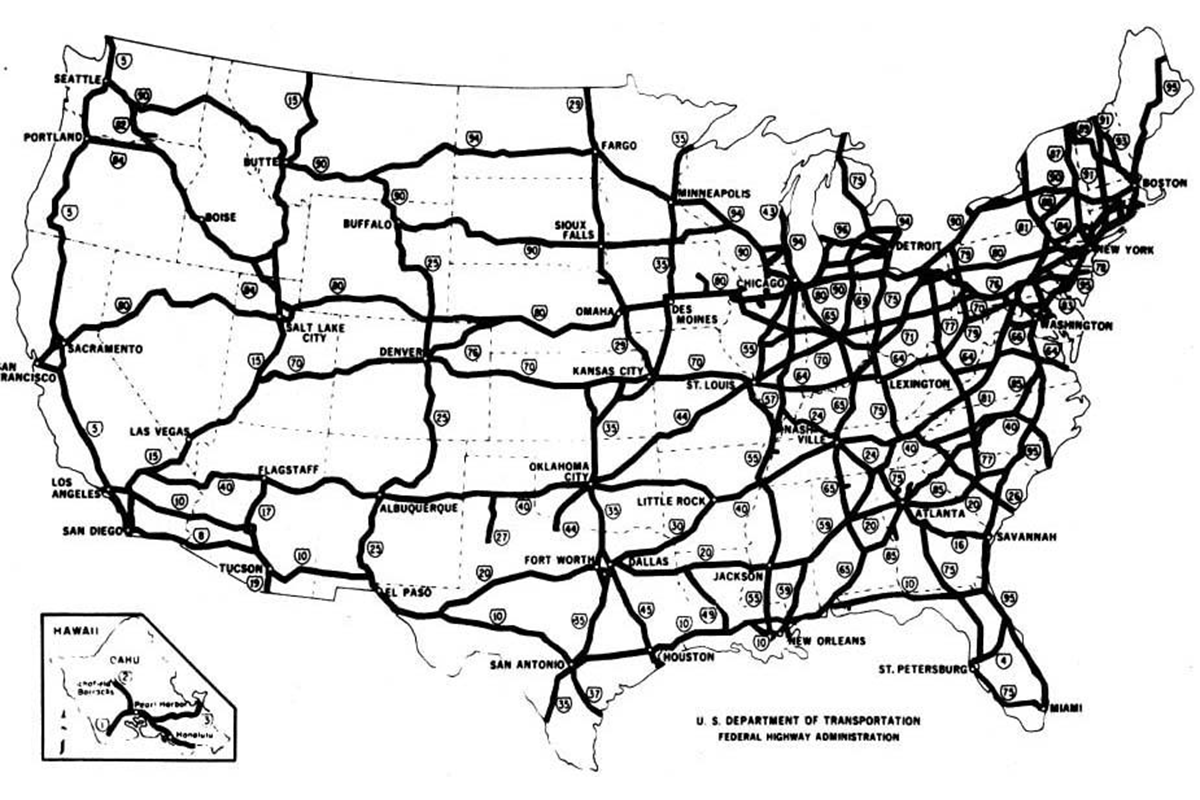

With the advent of the automobile and airplane in post-WWII American life came the decline of the passenger railroad. Also, while the federally funded interstate highway system of the 1950s never dislodged freight rail as the primary means by which goods were shipped long distance, it drastically reduced freight rail’s market share. Interestingly, the Interstate Highway System was first envisioned by President Eisenhower when he was a young Lieutenant Colonel in 1919 driving cross country on behalf of the Army on dreadful local roads.

The advent of the automobile and the post-WWII suburb caused a similar decline in ridership on interurban rail. Rather than responding to falling demand with increased investment to attract lost ridership local transit agencies responded to revenue shortfalls with budget cuts, thereby worsening services and leading to a vicious cycle of continued falling ridership.

After WWII, dozens of railroads merged and shed lines in an effort to survive in a new age of increased competition. Through these mergers were formed the remaining major profitable Class I freight railroads in the United States today: CSX, Norfolk Southern, BNSF, and Union Pacific. However, passenger rail proved unsustainable in the private market during these years as major rail companies concluded that carrying freight was more lucrative.

AMTRAK and the Northeast Corridor

Except for a brief period during WWI, the US government did not play a direct role in the operation and maintenance of the nation’s railways until the creation of Amtrak in 1971. In 1970, the Penn Central Railroad (which in more prosperous times had built both Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal) declared bankruptcy. It was the largest corporate bankruptcy in U.S. history up to that point. In 1971, Congress created Amtrak as a public corporation to maintain and operate intercity passenger rail service for medium and long distances. Amtrak (a combination of ‘American’ and ‘track’) absorbed several existing ailing local and regional passenger lines. While Amtrak’s operations were not always easy (it had to shed many routes and thousands of miles in the beginning), Amtrak’s ridership of roughly 15 million in the 1970s more than doubled to over 31 million in fiscal year 2017.

Amtrak’s busiest region is the Northeast Corridor (NEC). In 2000, Amtrak debuted its Acela line, the first high-speed rail (HSR) line in the United States. However, because the right-of-ways for the line are old, insufficiently straight, and often shared by slower freight trains, the Acela cannot reach the high speeds of comparable rail in Europe and Asia. Moreover, due to the winding nature of this particular right-of-way, the Acela cannot reach its speed potential for the majority of the Northeast Corridor.

Amtrak plans to replace current Acela train sets with new train sets by 2021. In addition, the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) has outlined plan’s, dubbed NEC Future, to upgrade rail infrastructure along the Northeast Corridor. This vision, at an estimated cost of $131 to $136 billion, includes improved service and performance objectives for frequency, travel time, design speed, and passenger convenience, corridor-wide repair, replacement, and rehabilitation of the existing NEC to bring the corridor into a state of good repair and increase reliability. Furthermore, NEC Future calls for “additional infrastructure between Washington, D.C., and New Haven, CT, and between Providence, RI, and Boston, MA, as needed to achieve the service and performance objectives, including investments that add capacity, increase speeds, and eliminate chokepoints.”

Nevertheless, despite this planning and investment, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) still notes that much of the NEC’s infrastructure is beyond its useful life. According to ASCE, “U.S. rail still faces clear challenges, most notably in passenger rail, which faces the dual problems of aging infrastructure and insufficient funding.” As stated by the Northeast Corridor Commission (a Congressional organization established to develop coordinated strategies for improving the NEC’s rail network), “…the NEC has hundreds of miles of aging track bed, hundreds of century-old small bridges, over a dozen century-old major bridges and tunnels, and power supply and signal systems that still rely on 1930s technology… we must bear in mind that future work to replace these assets will require more sacrifice in the form of disruptions to existing train services.”

The Promising Future of Trains in the USA

While it is encouraging that Amtrak ridership is up, the future of passenger rail in the United States is not confined to Amtrak. A privately financed bullet train is coming to Texas in the very near future. Developers in Texas are currently planning to deploy Japanese HSR technology developed by Central Japan Railway Company (JRC). Texas Central also recently announced that they recruited Spanish HSR operator Renfe as their operating partner. By 2024, passengers will be able to travel from Dallas to Houston in 90 minutes on a 200mph train.

While it is encouraging that Amtrak ridership is up, the future of passenger rail in the United States is not confined to Amtrak. A privately financed bullet train is coming to Texas in the very near future. Developers in Texas are currently planning to deploy Japanese HSR technology developed by Central Japan Railway Company (JRC). Texas Central also recently announced that they recruited Spanish HSR operator Renfe as their operating partner. By 2024, passengers will be able to travel from Dallas to Houston in 90 minutes on a 200mph train.

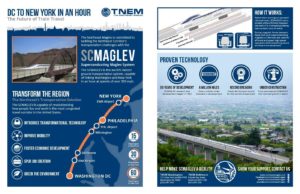

Meanwhile, back in the Northeast Corrdior, the planned SCMAGLEV project, with a top operating speed of 311mph and a cruising speed of over 300mph, will one day allow passengers to go from Washington, DC to New York City in one hour; all while avoiding the NEC’s traffic-congested roads and airport hassles. The first leg of this route will go from Washington, DC to Baltimore with an intermittent stop at BWI airport in a mere fifteen minutes. This initial phase is currently undergoing environmental impact study overseen by a host of federal, state, and local organizations, including the Federal Railroad Administration and Maryland Department of Transportation.

The future of train travel in the United States is bright. Indeed, it is in the midst of a comeback.