China Proves the Economic Benefits to Investing in High Speed Rail

In the 1950s, Americans and Europeans were paving asphalt and looking to the air for the next major leaps in transportation. With the personal freedom of cars and the speed of airplanes, the ships and trains of the past looked slow and outdated.

However, while the U.S. shut down railways and poured billions into paving highways, Japan spent billions blasting through mountains to make way for a specialized railroad. The Japanese public was also skeptical of trains, though, feeling more inclined to promote the modern air travel that the U.S. and Europe invested in. Nevertheless, Shinji Sogō, President of Japanese National Railways, pursued the vision of a new high speed train and the project commenced.

Despite being massively over budget, the first line between Tokyo and Osaka finished in 1964. This was the beginning of the Shinkansen, or “Bullet Train”. Hours were shaved off of existing route durations and continual improvements decreased this year after year.

The line had serviced over 100 million people just three years into its operation and a billion by 1976.

Railways are certainly not the primary mode of transportation in America, but several nations around the world have discovered a newfound appreciation for them.

When looking at high speed rail development, one country making enormous strides over the past decade is China.

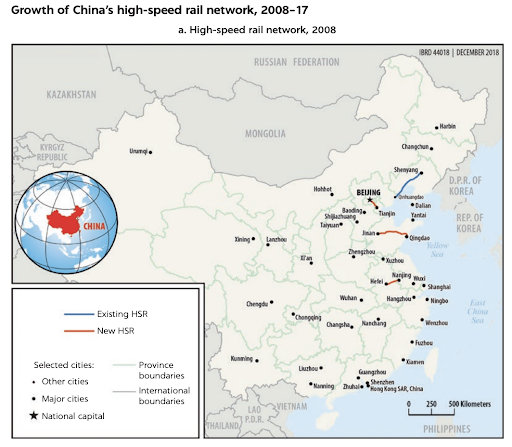

Despite having little HSR in the 2000s, by December 2014 the World Bank wrote, “in terms of high speed rail (HSR) network length, no country comes close to China.” With the 2008 financial crisis dragging down global economies, China sought to undertake massive infrastructure projects to maintain economic development and productivity. Making their first of many new generation HSR lines in August 2008, the Beijing-Tianjin line “quickly established itself as a competitive form of transport, carrying over 16 million passengers in its first full year of operation.”

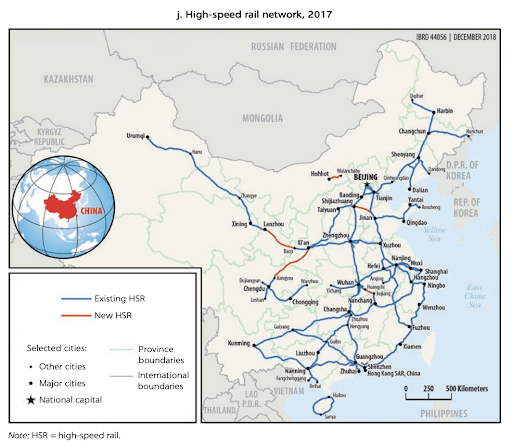

Opening a major long-distance route in 2009, “by December 2012, both the 1,318 km Beijing–Shanghai line and the 2,105 km Beijing–Guangzhou line had been completed, connecting the three most dynamic economic clusters in China.” With an original intent of increasing transportation capacity, HSR development in China has steadily become about connecting the nation’s economic centers and helping urbanize the surrounding cities and towns.

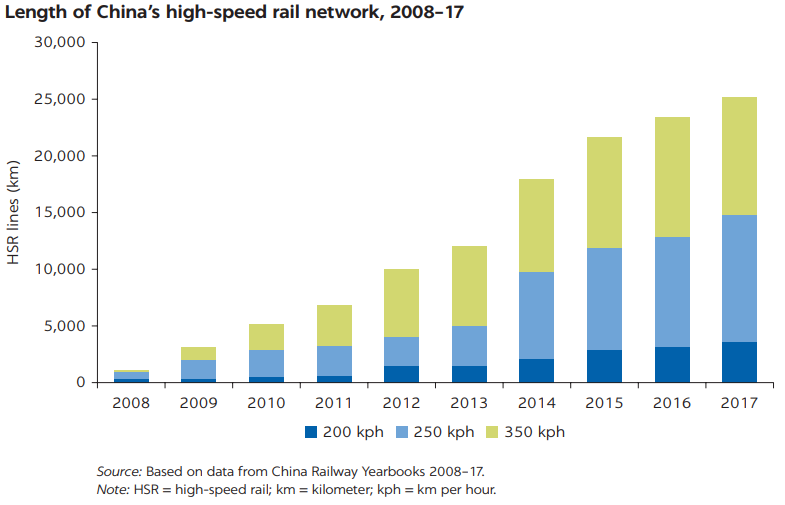

The following charts from the World Bank demonstrate the significant investments made in HSR development throughout China over the past decade.

With this increased service between cities, many shorter routes are taking dominance over air routes.

“Some short-distance air services have been completely withdrawn after an HSR line has opened; others have discounted fares or have reduced services to one or two flights each day,” according to the World Bank. This means that increasing capacity at airports will not be as much of a concern for local planners. Instead, planning around rail stations is becoming more important as the nation’s railways become more expansive.

On this note, HSR has spurred great developments for economic hubs and their nearby, smaller cities.

“All else being equal, a new business located within daily reach of such hubs will be more accessible to a larger pool of labor and other businesses, raising productivity,” the U.K. Department for Transport finds. Furthermore, the World Bank outlines how HSR is promoting growth outside of the economic centers. While smaller cities centered around one industry may have been losing workers to larger cities, this has caused density and environmental issues which hurt businesses. Therefore, “HSR aims to reverse this situation by providing a transport backbone that will stimulate complementarity between its cities and allow talent and technology to be devolved to smaller centers to improve their overall competitiveness.”

In many small or medium sized cities, municipal leaders have created “HSR new town” development plans; these plans seek to improve underdeveloped areas by developing land around a new HSR station. With at least 139 “HSR new towns” in China, local governments have seen greatly increased revenue from land sales – land values have increased by 3% to 13% in cases studied. However, the key to a successful plan is to keep the town well connected to existing urban areas and not oversupply the new real estate market.

To gain a better perspective of how new HSR projects affect locals, The Economist spoke to Gu Zhen’an who has spent 25 years in road construction. After finishing a highway connection to a new HSR station in a quiet part of town, he decided to get into real estate. With little business and few people, he bought cheap land around the new station, expecting the new city to sprawl up in the near future.

His rationale? With tens of thousands of miles of high speed rail, wherever China expands its network, offices and apartment buildings follow. With the expansion of HSR networks around Shanghai, for example, over 75 million people are within an hour commute of the metropolis.

While financing these projects will always be a concern, HSR provides a sustainable path to urbanizing many smaller towns and cities and links millions of workers to markets that are now not so far away.

Now more than ever, we need your help to make the project a reality. Be sure to sign our petition, and write letters to your legislators. Keep track of what we’re up to by following us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.