From the B&O to the Transcontinental Railroad to the Northeast Maglev

A century ago the United States was a world leader in railway deployment and use. While freight rail remains a productive enterprise in the U.S., American passenger rail today has not kept pace with Europe and Asia. What happened to the great American railroad? Recent high-speed rail developments in California, Florida, Texas and superconducting maglev train technology along the Northeast Corridor indicate that a comeback is in the works.

Rail Beginnings

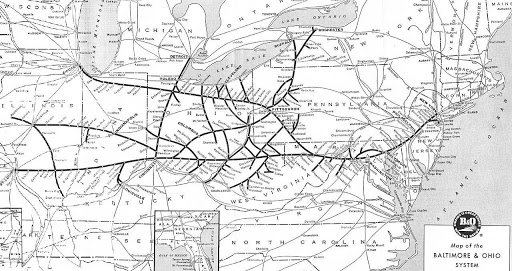

Chartered in 1827 and opened in 1830, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (B&O) was the first common carrier railroad and the first railroad open to the public in the United States. Initially, the B&O served the Maryland region and gradually expanded in the 1830s to Washington DC, Virginia, and West Virginia along the Ohio River. In the decades following its creation, the B&O grew to cover large swaths of the Northeast and Midwest, becoming one of the largest railroads of the 19th century along with others such as the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Union Pacific.

In the mid-19th century, numerous other companies soon followed the B&O and added miles of track and expanded the capacity for the transportation of goods and people. Though early American railroads often received public monetary subsidies or land grants from the government, the railroad industry in the United States developed and grew almost entirely in the private sector. In Europe, the government often nationalized and took direct control of the railways.

A confluence of factors led to astonishingly rapid growth in the railroad sector in the U.S. during the 19th century. The development of the steam engine powered the necessary trains. Also, the industrial revolution and related explosion in manufacturing necessitated the movement of raw materials and finished products. The burgeoning railroads were in competition with early canals such as the Erie Canal for the very lucrative business of transporting goods. However, the railroads were far more efficient than the canals for the purpose of transportation and consequently dominated the landscape.

For those readers in the DC-Baltimore metro area more interested in the history and legacy of rail in the U.S., be sure to visit the B&O Railroad Museum in Baltimore, MD.

The First Transcontinental Railroad: 1862-1869

In the midst of the Civil War, the Union recognized how integral rail lines were to supply lines and the transport of troops. The government also keenly recognized how important rail lines were going to be for the future of commerce after the war. In 1862, the country was cash poor but land rich. In 1862, the Congress passed and President Lincoln signed the Pacific Railroad Act. The law promoted the first transcontinental railroad. The government issued bonds and the law chartered the Central Pacific Railroad in Sacramento, California and the Union Pacific Railroad in Omaha, Nebraska. The law spurred these to link to each other. The Central Pacific built eastward and the Union Pacific built westward. The railroads were granted ownership of the land upon which their tracks traversed as well as sections of adjoining acres for whatever purpose they desired (land speculation could be highly lucrative). Therefore, both corporations had a strong financial incentive to lay as much track as humanly possible.

Because most able-bodied men east of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers were involved in the Civil War until 1865, most track was not laid until after the war. Numbering in the thousands, most workers for the Union Pacific were newly arrived Irish immigrants. For the Central Pacific, most workers were Chinese immigrants who had gone to California during the Gold Rush of the late 1840s. Racism was rampant. White workers were paid more than Chinese workers and white workers were given supervisory status over Chinese workers. Working conditions were abysmal. Aside from the long hours and grueling manual labor, many workers died as a result of explosions detonated to blast through mountains such as those of California’s Sierra Nevada range.

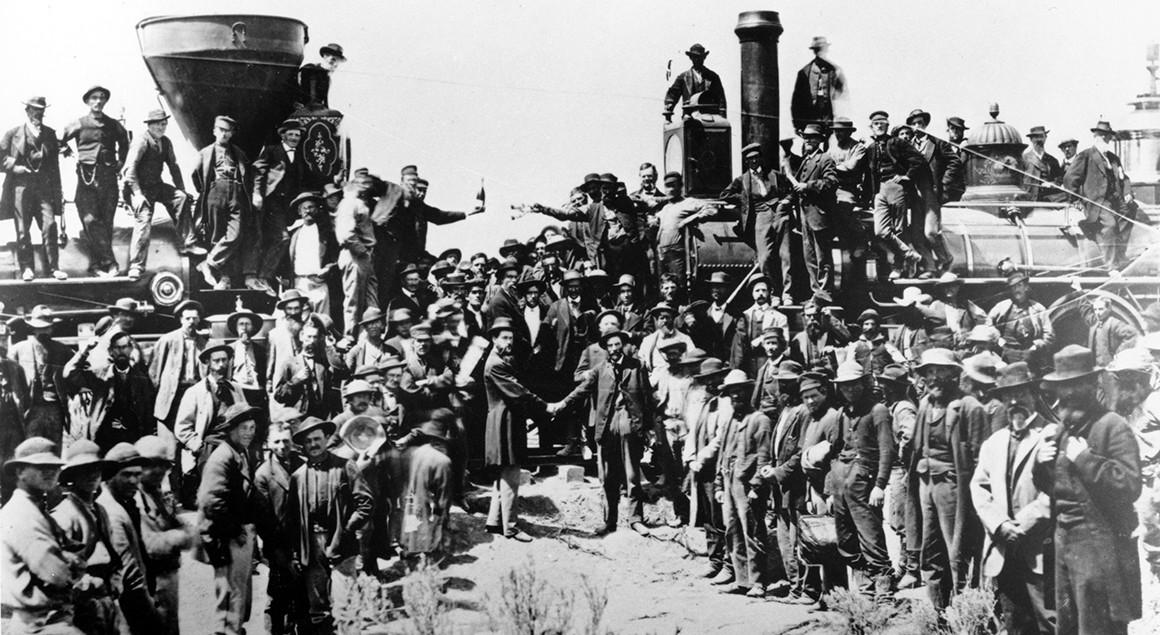

On May 10, 1869, the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific met and linked at Promontory, Utah (north of Salt Lake). They met 690 track miles east of Sacramento and 1086 miles west of Omaha. Shortly after driving the last spike, telegraph messages went out to the world proclaiming a new age in transcontinental travel and commerce. No longer would travelers from the East Coast have to sail below South America or make the physically harrowing trek of crossing the Panamanian isthmus to reach the West Coast. In a new and technologically awe-inspiring fashion, the continental United States was finally united.

Strikes, Robber Barons, and the ICC

As railroads continued to grow throughout the latter half of the 19th century, and as they became more interconnected with other business and more people relied on them for their livelihoods (from workers to traders to manufacturers to farmers), railroads gained economic and political power. Run by the ruthless Robber Barons of the Gilded Age (such as Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, Leland Stanford, and E.H. Harriman among others) the railroad corporations sometimes behaved very badly with the power they had accrued.

In 1877, after the B&O reduced wages for the third time, its workers in West Virginia went on strike. The governor sent in state militia units to break the strike, but the soldiers refused to fire on the workers. Subsequently, the governor called on federal troops. In the meantime, to protest wages and deplorable working conditions, strikes broke out on other rail lines. Strikes also broke out in other states such as Maryland, New York, Illinois, Missouri, and Pennsylvania. All forms of industry suffered. Riots erupted in urban centers and workers burned train depots all across the country. Ultimately, President Rutherford Hayes marshaled federal troops alongside various state militias and suppressed the strikers and their sympathizers. Many government officials feared a revolution was on the horizon. The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 ended after 45 days. Over 100 people were killed in the unrest.

Regulation of the railroads going forward was both important and fraught with tension. Because many railroads functioned as effective monopolies, they were able to price-gouge the public and the businesses that needed to utilize their services. Hence, the U.S. Congress created the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) as part of the Interstate Commerce Act of 1877. The ICC would regulate the railroads and work to ensure fair rates and eliminate rate discrimination. Its powers were transferred to the Surface Transportation Board in 1996.

We’ll be continuing this series with a post on the decline of the American Railroad, stay tuned! Make sure you subscribe to our emails and follow us on social media to keep with the latest news.